Socially responsible investments: a rapidly growing sector

Global warming, social injustice, planned obsolescence, certain products’ hidden toxicity, non-renewable energy and undemocratic government are among the many topics which regularly make the headlines.

Once considered only as a necessary means for achieving yield or wealth preservation objectives, financial markets have always enabled investors to bring a moral dimension to the way they choose to invest their savings.

The apparently complex financial sector (historically quite opaque for private investors), the many and varied scandals caused by listed companies, and major international treaties such as the Paris Climate Agreements, have all enabled investors to understand the leverage available to them through their savings and, especially, to consider the value of their investments in terms of an additional objective, rather than merely a search for financial gain. Financial service providers today are promoting “Ethical”, “socially responsible” or “ESG” (Environmental, Social and Governance) investments.

The history of socially responsible investment

Its origins go back to the 18th century, when the protestant community of the Quakers, who became rich traders and industrialists and were guided by their belief in justice and social equality, took a stand against the arms industry, and opposed slavery. Consistent in their principles, the Quakers practised their beliefs by being concerned about the way the businesses they owned were managed, by their respect for contractual agreements and the rights of their employees, and by providing access to education and healthcare for their families.

In 1928, the Evangelical Church of America created the Pioneer Fund, which does not invest in companies associated with alcohol or tobacco. Thus, the concept of “sin stocks”- and the first investment fund with deliberately ethical considerations - was born.

One of the positive effects of today’s rapid exchanges of information is that we are now collectively aware of the climate emergency, and of the multiple social injustices and unacceptable behaviour of many companies or countries which for many years have lain hidden in the shadows.

In 2000, the United Nations adopted the Global Compact which aims to encourage companies around the world to adopt a socially responsible attitude by undertaking to adopt and promote several principles which concern human rights, international employment standards, the environment, and the fight against corruption. The signing of this compact is still voluntary for companies.

In 2006, the United Nations went further by promulgating the UNPRI (United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment). These UNPRIs clearly mark the revival of socially responsible investment, since they require the signatories (currently more than 1,600) to be transparent in the way they manage their clients' assets, representing more than 60 trillion in assets under management.

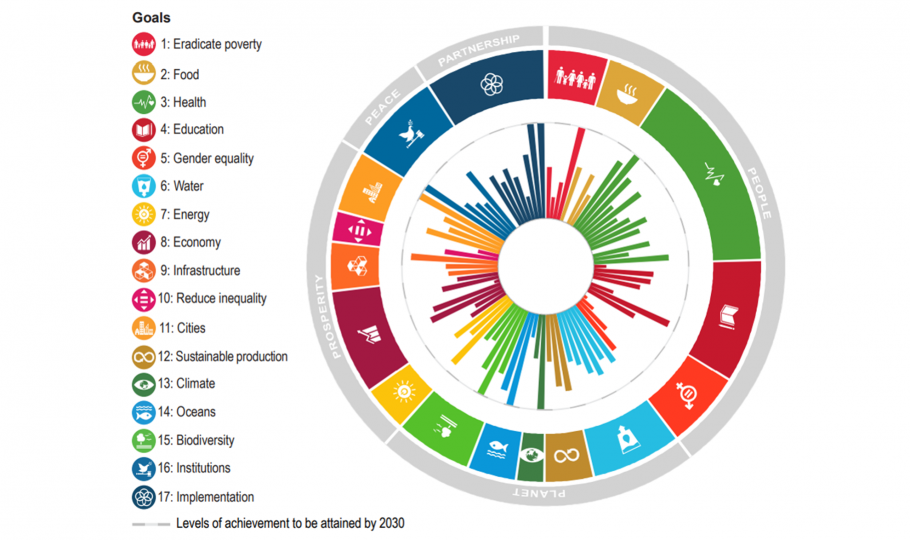

Under the impetus of these treaties and of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (see, illustration) and given companies’ obligations to comply with recycling, pollution and other constraints in the future, the most innovative companies in these areas will inevitably, become the best positioned, compared with their competitors.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

In view of these considerations, which options are available to investors who want to choose investments with a responsible approach?

The most widely accepted way is to eliminate from their investment universe a whole series of companies whose products or behaviour should be discouraged. The most obvious are companies which do not respect the United Nations Global Compact, or those involved in non-conventional weapons, tobacco, fossil fuels and non-conventional oil and gas extraction or an energy mix which does not encourage renewable energy. Some analyses then go further by analysing additional factors such as biodiversity, nuclear energy, water use, taxation, oppressive regimes, the death penalty and speculation on agricultural commodities.

Finally, once a thorough analysis has been made of the companies and countries which constitute the investment universe, a ranking of the most irreproachable of them can be established. As a result, an increasing number of non-financial data providers have emerged, the most reputable of which are MSCI and Sustainalytics, among others. Thanks to the information which they have obtained from the companies themselves - but also from other sources, such as the press, NGOs, impact studies or teams of internal analysts - these data providers are able to give "sustainability" ratings for companies analysed on criteria relating to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG), but also on the controversies in which these companies or countries are involved.

The type of management resulting from these analyses is usually called "Positive Screening" or "Best in Class", i.e. the manager will only include in his portfolios the best players in terms of the non-financial criteria targeted by his management. An increasing number of managers are also proposing shareholder engagement policies, through which they engage in active dialogue with companies to encourage them to make the necessary efforts on matters relating to the way they conduct their business.

The techniques mentioned above can be applied to all types of portfolios. However, an increasing number of other management options are available because they may be more relevant in the eyes of some investors: thus many thematic funds have emerged targeting specific themes relating to Millennium Development Goals, including environmental funds, gender funds, respectful personnel management policies, etc.

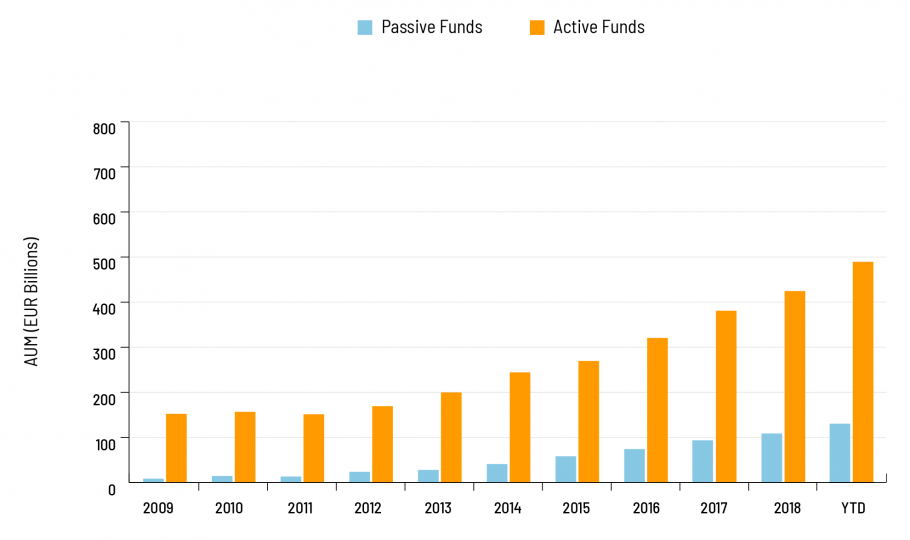

Demand increases: investing sustainably becomes the norm

For many years now, pooled funds have emerged through which part of the fund's assets (generally 10%) are invested directly in so-called social enterprises, or projects in which the social purpose takes precedence over the financial return. Such pooled types funds have made it possible to finance many projects which may not have been possible without them.

Finally, in recent years, impact funds have emerged, through which a social return is generated in parallel with a financial return. Unfortunately, most of these funds, which invest directly in unlisted projects, are not accessible to the general public and are reserved for qualified investors. However, innovative solutions have also emerged through which, at the initiative of suppliers, a very tangible and participatory impact is generated. These solutions, which are still rare, are increasing in number because they enable investors to link their investment directly to an impact on the real economy, which is often absent in the investment world.

As we have seen, sustainable investment solutions are increasing every day, and will probably become the norm in the coming years. Many new eco-type labels are emerging around the world, helping to guide investors in their choices. A preference should be given to national labels, which are more objective in nature. In any event, this tendency - far from being a fad - empowers all investors to make objective decisions about the impact generated by their investments.

Investing sustainably is no longer a trend but a norm. Recent years have seen the emergence of numerous funds that integrate ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) criteria into their management methods. The policyholder of a Luxembourg life insurance policy can integrate so-called ethical or socially responsible investments into the life insurance contract while respecting the risk profile.